The Seventeenth Century: Great Cathedrals and the Rise of a Popular Baroque

Marked not by conquest but hegemony, Mexico of the sixteen hundreds was a long siesta of relative peace. Social upheavals were confined, as were intrusions by Spain's competing European powers, France and Great Britain. By the onset of the century most of Mexico had been pacified, the vast majority of its many distinct indigenous peoples converted, and order established and maintained by way of the oppressive encomienda system. Incidents of apostasy were infrequent, as the Church continued to consolidate its power and wealth, mostly in the form of great tracts of land and became New Spain's fiscal agent, supreme in both physical resources and spiritual authority.

“This abundant wealth and easy command of artisan and manual labor enabled the Church to transform cities and hamlets, especially in the core region of Mexico, into an immense museum of Baroque architecture and art which remains a patrimony of the modern nation. {...}Thus the Church acquired a position, particularly in the seventeenth century, that became almost impregnable and highly resistant to the effects of modern secularism”. (Leonard, Irving. Baroque Times in Old Mexico, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1959, p. 221)

The Push Northward

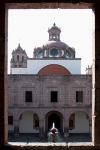

Loreto, Baja California Sur, Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó, façade & rectory Only along New Spain's expanding Northern frontier did missionaries and settlers struggle to establish and defend themselves. From Sonora and California to Texas, intrepid Jesuit priests such as Eusebio Kino (1644-1711) and Franciscan friars like Alonso de Benavides and Damián Massanet ventured into the unknown to set up mission outposts. Only seventy-one years after Pope Paul III recognized the order of the Society of Jesus (in Rome in 1540) and only thirty-nine years their arrival in Mexico City (1572), the Jesuits had reached the Tarahumara Amerindians in Chihuahua. Three years later they were amongst the Mayo of Sonora, and finally by 1683 had established a mission-fort near Loreto, Baja California.

Loreto, Baja California Sur, Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó, façade & rectory Only along New Spain's expanding Northern frontier did missionaries and settlers struggle to establish and defend themselves. From Sonora and California to Texas, intrepid Jesuit priests such as Eusebio Kino (1644-1711) and Franciscan friars like Alonso de Benavides and Damián Massanet ventured into the unknown to set up mission outposts. Only seventy-one years after Pope Paul III recognized the order of the Society of Jesus (in Rome in 1540) and only thirty-nine years their arrival in Mexico City (1572), the Jesuits had reached the Tarahumara Amerindians in Chihuahua. Three years later they were amongst the Mayo of Sonora, and finally by 1683 had established a mission-fort near Loreto, Baja California.

Creole settlers followed while garrison captains endeavored to protect these fledgling communities against local Indian resistance, which ranged from the Pima of the Southwest to the Comanche of the Plains. The results could be tragic, as in the case of the famous Pueblo Revolt of 1680 when indigenous leader Popé rallied local New Mexican tribes (including the Hopi and Zuni) against Governor Antonio de Otermín (in office, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1679-1683). By September of that year all Spanish settlements had been destroyed, twenty-one of the thirty-three Franciscan missionaries in New Mexico had been killed, and the Spanish were in retreat to El Paso, Texas. The tricentennial of the Pueblo Revolt was ardently commemorated by the current-day Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, who have succeeded where other tribes have failed in perpetuating their pre-Colombian traditions.

Isleta Pueblo, New Mexico, San Agustín, bell-towerFrom the time Sieur de La Salle (1643-1687) navigated down the Mississippi from Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico (1682), Spain was forced to stave off French intrusions from the East in what were lands that now belong to the United States. A year after La Salle’s expedition, in May of 1683 the Dutch buccaneer Laurent de Graff (circa 1653-1704), infamously known as Lorencillo, sacked the port city of Veracruz and made off with some 150 hostages and a booty estimated at seven million pesos. Such brazen piracy hearkened back a century when in 1568 British pirate John Hawkins (1532-1595) raided Veracruz while his countryman and cousin Francis Drake (1540-1595) terrorized both Mexico’s Pacific and Gulf coasts, pillaging at will and with astounding speed and stealth. Mexico was once again shocked, this time by Lorencillo’s plundering of Veracruz. Guarded by the mighty island fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, this maritime entrepôt was a veritable monument to Cortés’ conquest.

Isleta Pueblo, New Mexico, San Agustín, bell-towerFrom the time Sieur de La Salle (1643-1687) navigated down the Mississippi from Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico (1682), Spain was forced to stave off French intrusions from the East in what were lands that now belong to the United States. A year after La Salle’s expedition, in May of 1683 the Dutch buccaneer Laurent de Graff (circa 1653-1704), infamously known as Lorencillo, sacked the port city of Veracruz and made off with some 150 hostages and a booty estimated at seven million pesos. Such brazen piracy hearkened back a century when in 1568 British pirate John Hawkins (1532-1595) raided Veracruz while his countryman and cousin Francis Drake (1540-1595) terrorized both Mexico’s Pacific and Gulf coasts, pillaging at will and with astounding speed and stealth. Mexico was once again shocked, this time by Lorencillo’s plundering of Veracruz. Guarded by the mighty island fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, this maritime entrepôt was a veritable monument to Cortés’ conquest.

“Cortés, pleased with the manners of the people and the goodly reports of the land, resolved to take up his quarters here for the present. The next morning, April 12, being Good Friday, he landed, with all his force, on the very spot where now stands the modern city of Vera Cruz. Little did the Conqueror imagine that the desolate beach on which he first planted his foot was one day to be covered by a flourishing city, the great mart of European and Oriental trade, the commercial capital of New Spain.” (Prescott, William Hickling, History of the Conquest of Mexico, Phoenix Press, London, 2002, p. 142; first published by Harper & Brothers, New York, 1843)

The Man of Sorrows

While ports and frontiers intermittently demonstrated vulnerability, the heartland remained stable. A form of Russian serfdom had evolved, in which the indigenous peoples were permanently indentured to great landed estates. These latifundia or estancias were originally allotted to conquistadors and their cohorts, and then passed on to their descendants. They were maintained through the system of encomienda, whereby landowners held rights to the tributes of a native community in exchange for presumption of protection and for ensuring them a Christian education. In the early seventeenth century the Mexican encomienda was largely replaced by repartamiento and ultimately evolved into the notorious system of social organization and agrarian capitalism known as the hacienda.

Ahualulco de Mercado, Jalisco, hacienda del Carmen, casa grande This feudal system had succeeded in fending off intense royal and ecclesiastic criticism. Nearly a century after the discord at Valladolid, where progressive humanism won out over exclusive theology, King Philip IV (1621-1665) sounded the death knell to any notion of Amerindian autonomy in the form of the ‘settlement tax’. While disadvantageous, even detrimental to the average if not impecunious Creole farmer of the mid seventeenth century, this special tax was a windfall for the wealthy landowners. In recompense for royalties already incurred, the King recertified their old and defective estancia land titles, thus safeguarding the ample extent of their territory and guaranteeing their peon native workforce in perpetuum.

Ahualulco de Mercado, Jalisco, hacienda del Carmen, casa grande This feudal system had succeeded in fending off intense royal and ecclesiastic criticism. Nearly a century after the discord at Valladolid, where progressive humanism won out over exclusive theology, King Philip IV (1621-1665) sounded the death knell to any notion of Amerindian autonomy in the form of the ‘settlement tax’. While disadvantageous, even detrimental to the average if not impecunious Creole farmer of the mid seventeenth century, this special tax was a windfall for the wealthy landowners. In recompense for royalties already incurred, the King recertified their old and defective estancia land titles, thus safeguarding the ample extent of their territory and guaranteeing their peon native workforce in perpetuum.

“The settlement tax constitutes one of the most important events in the seventeenth century. Its consequences were far-reaching. The country was impoverished, to be sure; but at the same time the great estates attained their definitive boundaries and were ensured continuing, even heightened, predominance. The new title deeds were like a Magna Charta for the rural hacienda; its status had been strengthened and its territory considerably enlarged”. (Chevalier, François. Land and Society in Colonial Mexico: The Great Hacienda, translated by Alvin Eustis, edited, with foreword by Lesley Byrd Simpson, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1970, p. 277)

Oaxaca, Oaxaca, Santo Domingo, Capilla del Rosario, cupola The legitimization of these deeds officially made hacienda life permanent, and was a defining act in assuring class immobilization in an otherwise changing world. A social torpor and sustained hopelessness defined the campesino’s condition. His subjection was total. One wonders if the native sculptor transposed this Medieval melancholia onto the expression of Christ himself in the favored Mexican theme, Ecce Homo, ubiquitously displayed in Colonial Mexican statuary of this time. These Latin words were uttered by Pontius Pilate when Jesus was presented to him after his flagellation and mocking. Variants such as Our Lord of the Cane are also common, let alone the Christ of Patience where Jesus, battered and dejected, patiently awaits his Crucifixion. If not in outright penitential agony, the Man of Sorrows gazes beyond in soulful resignation.

Oaxaca, Oaxaca, Santo Domingo, Capilla del Rosario, cupola The legitimization of these deeds officially made hacienda life permanent, and was a defining act in assuring class immobilization in an otherwise changing world. A social torpor and sustained hopelessness defined the campesino’s condition. His subjection was total. One wonders if the native sculptor transposed this Medieval melancholia onto the expression of Christ himself in the favored Mexican theme, Ecce Homo, ubiquitously displayed in Colonial Mexican statuary of this time. These Latin words were uttered by Pontius Pilate when Jesus was presented to him after his flagellation and mocking. Variants such as Our Lord of the Cane are also common, let alone the Christ of Patience where Jesus, battered and dejected, patiently awaits his Crucifixion. If not in outright penitential agony, the Man of Sorrows gazes beyond in soulful resignation.

Inquisition and Illumination

By the end of the fifteen-hundreds, the genocidal effects of epidemics had reduced to a staggering degree Mexico’s native populations. An economic recession continued well into the seventeenth century. Amerindians lived in urban squalor, were fettered to great landed estates, or contracted out for paltry sums to work in the murderous conditions of the silver mines. In such a dystopia the Catholic Church represented an egalitarian institution, inasmuch as the Seven Sacraments, from Baptism to Extreme Unction, were bestowed unto indigenous or Creole alike, Spaniard or mestizo, man or woman. In order to ensure religious conformity, in 1570 King Philip II (1557-1598) established the Holy Office, historically known as the Inquisition and overseen in Mexico City by the Dominican order. This accord between the Holy Office and the Black Friars was already long-standing. Spanish himself, Dominic had been awarded his rule, the Order of Friars Preachers (in 1217 by Pope Honorius III), to continue his work eradicating heresy.

“Dominic (1170-1221), an Augustinian Canon himself at the time, was en route from Spain to Rome when he passed through an area of France particularly bothered by the Albigensian heresy, and realized that very little was being done to combat the spread of this heresy”. (Vidmar, John. The Catholic Church Through the Ages: A History, Paulist Press, New York, 2005, p. 134)

Cuquila, Oaxaca, Santa María, high altar, niche sculpture detail (top story right), St. Dominic In New Spain, the Inquisition was never as active nor as punitive as in Spain itself, where the humanist Juan Luis Vires (1492-1540) claimed one could neither speak nor remain silent without getting into trouble. In seventeenth century Mexico, the Holy Office’s efforts were usually directed towards prosecuting petty crimes having nothing to do with religious disloyalty. While perpetually skeptical of the natives' Christian veracity, what mostly drew the Inquisition’s attention was apprehension over the great Lutheran heresy and the possibility that it could proliferate throughout the Mexican population, i.e., the dread of Protestants, “the Red Communists or Islamic terrorists of the sixteenth century, as it were {…}, the New-World boogey-man” (Cruz, Joel Morales. The Mexican Reformation, Pickwick Publications, Eugene, Oregon, 2011, p. 131). In Europe the bloody Thirty Years War raged from 1618 to 1648, pitting Protestant versus Catholic, while in coeval Mexico a counter-reformationist still zeal took precedence over prosecuting heresy and weeding out necromancy. The culmination of the Inquisition’s retribution occurred at mid-century, when in 1649 thirteen of 109 accused individuals were put to death in Mexico City. Today one is reminded of the dark history of this institution by Mexico City’s magnificent Palace of the Inquisition, fittingly located across the Calle Brasil from the church of Santo Domingo.

Cuquila, Oaxaca, Santa María, high altar, niche sculpture detail (top story right), St. Dominic In New Spain, the Inquisition was never as active nor as punitive as in Spain itself, where the humanist Juan Luis Vires (1492-1540) claimed one could neither speak nor remain silent without getting into trouble. In seventeenth century Mexico, the Holy Office’s efforts were usually directed towards prosecuting petty crimes having nothing to do with religious disloyalty. While perpetually skeptical of the natives' Christian veracity, what mostly drew the Inquisition’s attention was apprehension over the great Lutheran heresy and the possibility that it could proliferate throughout the Mexican population, i.e., the dread of Protestants, “the Red Communists or Islamic terrorists of the sixteenth century, as it were {…}, the New-World boogey-man” (Cruz, Joel Morales. The Mexican Reformation, Pickwick Publications, Eugene, Oregon, 2011, p. 131). In Europe the bloody Thirty Years War raged from 1618 to 1648, pitting Protestant versus Catholic, while in coeval Mexico a counter-reformationist still zeal took precedence over prosecuting heresy and weeding out necromancy. The culmination of the Inquisition’s retribution occurred at mid-century, when in 1649 thirteen of 109 accused individuals were put to death in Mexico City. Today one is reminded of the dark history of this institution by Mexico City’s magnificent Palace of the Inquisition, fittingly located across the Calle Brasil from the church of Santo Domingo.

As diligently outlined by Irving Leonard in his Books of the Brave, in sharp contrast to these exacting censorial activities there appears to have been a reasonably active book trade in sixteen-hundreds Mexico which serviced the country’s modest class of intelligentsia. The Creole lay-priest Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700) was one of a handful of scholars able to visualize the increasingly relative place man held in the universe. Like a Renaissance Humanist, he was a man of great erudition and many interests beyond theology. In 1690, he published the treatise Astronomical and Philosophical Libra in which he dared ascribe the origins of the comet of ten years prior (which had so terrified and perplexed millions of Mexicans) to science. Such clerical heresy put Sigüenza y Góngora at direct odds with his illustrious fellow Jesuit, the aforementioned Eusebio Kino (1645-1711), who upheld the ancient and unsubstantiated notion that comets represented sinister celestial portents.

Suchixtlauca, Oaxaca, San Cristóbal, façade relief, Dominican insigniaExhibiting a remarkable curiosity for the unfamiliar, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora dedicated himself to the preservation of pre-Hispanic languages and accumulated a vast collection of books, documents, maps and artifacts referencing indigenous cultures, writing his own version of the History of the Chichimec Indians (tragically lost). In Glories of Querétaro he intercalated Náhuatl words in his lengthy descriptions of the ‘mascarada’ celebration on occasion of the 1680 dedication of that city’s sanctuary La Congregación de Nuestra Señora de la Guadalupe (now simply referred to as La Congregación). Because of his scholastic achievements in resurrecting his country’s pre-Colombian past, Sigüenza y Góngora came to embody a newfound, independent (from Spain) feeling amongst his fellow Creoles with respect to their shared native Mexico. This sentiment of autonomy had already manifested itself in the aborted Creole conspiracy of 1566, a fiasco of an incident conceived by the scheming former conquistador Alonso de Avila (1486-1566) which was to have been led by Martín Cortés (circa 1523-circa 1595) who, as son of both Hernán and La Malinche, was and is considered Mexico’s first mestizo. Nevertheless, in the century that followed, "the Creole is significant for having spawned and developed an American identity, the very origins of Mexicanness". (personal translation Vargaslugas, Elisa, México Barroco, vida y arte, Salvat Editores, Grolier Editores, Querétaro, 1993, pps. 21-22)

Suchixtlauca, Oaxaca, San Cristóbal, façade relief, Dominican insigniaExhibiting a remarkable curiosity for the unfamiliar, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora dedicated himself to the preservation of pre-Hispanic languages and accumulated a vast collection of books, documents, maps and artifacts referencing indigenous cultures, writing his own version of the History of the Chichimec Indians (tragically lost). In Glories of Querétaro he intercalated Náhuatl words in his lengthy descriptions of the ‘mascarada’ celebration on occasion of the 1680 dedication of that city’s sanctuary La Congregación de Nuestra Señora de la Guadalupe (now simply referred to as La Congregación). Because of his scholastic achievements in resurrecting his country’s pre-Colombian past, Sigüenza y Góngora came to embody a newfound, independent (from Spain) feeling amongst his fellow Creoles with respect to their shared native Mexico. This sentiment of autonomy had already manifested itself in the aborted Creole conspiracy of 1566, a fiasco of an incident conceived by the scheming former conquistador Alonso de Avila (1486-1566) which was to have been led by Martín Cortés (circa 1523-circa 1595) who, as son of both Hernán and La Malinche, was and is considered Mexico’s first mestizo. Nevertheless, in the century that followed, "the Creole is significant for having spawned and developed an American identity, the very origins of Mexicanness". (personal translation Vargaslugas, Elisa, México Barroco, vida y arte, Salvat Editores, Grolier Editores, Querétaro, 1993, pps. 21-22)

“Creoles, invoking Mexican history to legitimate their Mexican nationality, had much recourse to the accounts by sixteenth-century chroniclers, and later ones based upon them. Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morelos, insurgent leaders, had a historically based sense of Mexican nationality. Their movement, and new seigniorial reaction among landed Creoles in Mexico, at length succeeded, and in the 1820s, in capturing the land for Mexican nationals. (Liss, Peggy K. Mexico Under Spain, 1521-1556: Society and the Origins of Nationality, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1975, p. 156)

“For all their apparent irresponsibility, their poor aptitude for action, their serious limitations, the Creoles formed a world apart, a united world of new people whose interests and attitudes were not only different from, but irreconcilably opposed to, those of the Spaniards.” (Benítez, Fernando. The Century after Cortés, translated by Joan MacLean, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1965, p. 214)

It is in this spirit of national identity and solidarity some 130 years prior to Mexican independence that Sigüenza y Góngora wrote, in the epigraph of his publication Theater of Political Virtues that Constitute a Ruler (1680), the often revisited words, “Consideren lo suyo los que se empeñan en considerar lo ajeno; es más fácil juzgar que obrar y más fácil mirar desde la seguridad de la forteleza los peligros” (“Reflect on your own issues rather than effort to deliberate on those of others. Those who strive to judge others should first judge themselves; it is easier to judge than act, and easier to observe dangers behind the security of a fortress”. personal translation)

Undoubtedly the most outstanding Creole figure of late seventeenth century Mexico was Sigüenza y Góngora’s dear friend and intellectual confidant, the Carmelite nun Juana Inés de La Cruz (1648-1695). Spending the majority of her life within the cell walls of the convent of San Jéronimo in Mexico City, her spiritual and psychological nature is explored in Octavio Paz’s 1982 Sor Juana: Or, the Traps of Faith, in which the author frequently employs the word ‘indecible’ (unmentionable) to convey the heartrending aloneness of Juana’s misfit existence. Laboriously sublimating her passions to resemble conventional channels of emitting and receiving God’s love, Sor Juana subsisted in a self-defined dimension teetering between an intense sensuality and a remarkable capacity for ratiocination, opposing forces which both constantly collided with Church and society.

México, D.F., Castillo Chapultepec, posthumous portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera, detail Juana’s highly personal, alternative form of godly devotion may be likened to that of the great Christian mystics Saint Francis of Assisi (1182-1226) or Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-1582). Unlike her two predecessors, however, Juana would never be considered for beatification, as the temporal expression of her divinely devotion remained wholly inadmissible. Nowhere did the interweaving of Sister Juana’s intellectual and corporal sides express itself as movingly and precariously as in her poetry. Through her First Dream and her many ‘poemas de amor’, some of which were clearly addressed to other women, Juana’s spiritual paroxysms were played out on the page. An exceptional woman, she lived in a time and place where free expressions by women were eschewed, in a world unequipped to address the intensity and conspicuousness of her human contradictions.

México, D.F., Castillo Chapultepec, posthumous portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera, detail Juana’s highly personal, alternative form of godly devotion may be likened to that of the great Christian mystics Saint Francis of Assisi (1182-1226) or Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-1582). Unlike her two predecessors, however, Juana would never be considered for beatification, as the temporal expression of her divinely devotion remained wholly inadmissible. Nowhere did the interweaving of Sister Juana’s intellectual and corporal sides express itself as movingly and precariously as in her poetry. Through her First Dream and her many ‘poemas de amor’, some of which were clearly addressed to other women, Juana’s spiritual paroxysms were played out on the page. An exceptional woman, she lived in a time and place where free expressions by women were eschewed, in a world unequipped to address the intensity and conspicuousness of her human contradictions.

“In the medieval atmosphere of seventeenth century Mexico where women could not dream of independent lives, where it was axiomatic that they possessed inferior intelligence, and where they were scarcely more than chattel of their fathers, brothers, and husbands, intellectual curiosity in Sister Juana’s sex was not only indecorous but sinful. It might, indeed, be the workings of the Evil One and, therefore, imperil one’s salvation, as her superiors in the convent more than once assured her.” (Leonard, Irving. Baroque Times in Old Mexico, The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1959, p. 179)

Gazing into the youthful, arresting, yet doleful eyes of Sister Juana, as expressed in her portrait by the eighteenth century Mexican master Miguel Cabrera (1695-1768), one discerns an intellectually superior and socially estranged woman. After defying the censure of the Bishop of Puebla (Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, in office, 1767-1699) with an epistle known as her Respuesta (1691), in the end Sister Juana renounced all her beloved books and musical instruments, placed herself under extreme penitential discipline and, in renewing her vows, famously wrote and signed in her own blood, “Yo, la peor del mundo”. (“I, the worst in the world”.)

Figures like Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora and Juana Inés de la Cruz are historical treasures of Colonial Mexico. Extrinsic luminaries during their lives, they nevertheless remained circumscribed to the periphery of society. Their ultimate capitulation speaks not to personal shortcomings, but to the radical dualism of good and evil, right and wrong as defined by Catholic Spain, and how severely this polarity was underscored where they both lived. Suppressing individualism, ensuring communality, adhering to “the belief that truth was one and absolute, and that she held a clue to it, had for a century underlain Spain’s policy and directed all her energies at home and abroad.” (Atkinson, William C. A History of Spain and Portugal, Penguin Books, Baltimore, 1960, p. 168)

Philip’s Vision

Spain had harnessed the workforce of a new continent and, in a land thousands of miles away, erected cathedrals of such scale and opulence as to rival its own. Brought to fruition in the previous century by Charles V’s son King Philip II (1556-1598), Mexico truly was indeed Spain’s crowning achievement: a Neo-Medieval unity of religious order and feudal dominance. This unity was elegantly sheltered behind an architectural splendor which was the flowering of the Baroque in the New World, and masked its mother country’s steady course towards financial ruination.

Spain’s quest to be an insuperable and interminable empire had emptied the royal coffers. The illustrious Philip, inheritor of his father's vast empire, was the great hero of the naval Battle of Lepanto, when in 1571 his brother Don Juan of Austria lead a Christian coalition to victory over Ali Pasha’s Ottomans in the Levant’s Gulf of Lepanto. Atotonilco, Guanajuato, Santuario de Jesús Nazareno, Capilla del Rosario, groin vault webbing mural, Battle of Lepanto (one of two vault depictions)Seventeen years later his success over the infidel Moslems was eclipsed by a debacle at the hands of the loathed Protestants, with his great Armada falling victim to British naval superiority. Leaving a national debt of some 100 million ducats, ten times the amount required to have assembled the Armada, one of Philip’s last royal acts was to relinquish the Low Countries including his father’s beloved Flanders.

Atotonilco, Guanajuato, Santuario de Jesús Nazareno, Capilla del Rosario, groin vault webbing mural, Battle of Lepanto (one of two vault depictions)Seventeen years later his success over the infidel Moslems was eclipsed by a debacle at the hands of the loathed Protestants, with his great Armada falling victim to British naval superiority. Leaving a national debt of some 100 million ducats, ten times the amount required to have assembled the Armada, one of Philip’s last royal acts was to relinquish the Low Countries including his father’s beloved Flanders.

“Philip’s personality and the architecture of his reign are bound up inextricably with his interpretation of his religious responsibility. Melancholy and suspicious, but conscientious to a degree, he looked upon himself as God’s field-marshal upon earth to combat the great enemy of mankind, the Reformation; and he was determined to show God where Spain stood in the matter and to show the rest of Europe Spain’s power and his own nobility as the stern judge of man’s expression of religion”. (Sanford, Trent Elwood, The Story of Architecture in Mexico, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York, 1947, p. 111)

San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid (Spain), El Escorial, lateral façadeDecades earlier while still a virile man, Philip had left a lasting mark on Spanish architecture by commissioning the Escorial outside of Madrid, meant simultaneously as a court palace, personal summer retreat, monastery, school, library, and mausoleum to his father. Begun in 1557 to the plans of Juan Bautista de Toledo (?-1567) it was completed under the guidance of famed architect Juan de Herrera (ca. 1530-1597) and revealed an Italian influenced classical order. Though uninspired in its rigid, grid like geometry (unlike the Palace of Aranguez, a preceding Bautista de Toledo – Herrera cooperation), the Escorial was Spain’s greatest child of the Renaissance and ushered forth new design modules which would be implemented throughout the country and its colonies, and on a scale far exceeding its Italian prototypes.

San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid (Spain), El Escorial, lateral façadeDecades earlier while still a virile man, Philip had left a lasting mark on Spanish architecture by commissioning the Escorial outside of Madrid, meant simultaneously as a court palace, personal summer retreat, monastery, school, library, and mausoleum to his father. Begun in 1557 to the plans of Juan Bautista de Toledo (?-1567) it was completed under the guidance of famed architect Juan de Herrera (ca. 1530-1597) and revealed an Italian influenced classical order. Though uninspired in its rigid, grid like geometry (unlike the Palace of Aranguez, a preceding Bautista de Toledo – Herrera cooperation), the Escorial was Spain’s greatest child of the Renaissance and ushered forth new design modules which would be implemented throughout the country and its colonies, and on a scale far exceeding its Italian prototypes.

“The Renaissance was brought to Spain by Italian sculptors, by Italian works of art, and by Spanish, Flemish, and French sculptors trained in Italy. The arrival of Charles V (King of Spain and de facto from 1516 and de jure from 1518; German Emperor from 1520) stirred all of Spain to expectations of imperial splendor. Anticipating a large building programme, artists flocked to the peripatetic court”. (Kubler, George and Soria, Martín. Art and Architecture in Spain and Portugal and their American Dominions: 1500 to 1800, Penguin Books, Baltimore, 1959, p. 125)

In 1573 Philip issued his Ordenanza sobre descubrimiento nuevo y población (Ordinance on the Discovery of Towns). Although this mandate was decreed after certain important viceregal municipalities had already been founded, it served to standardize urban planning in Spain's New World colonies going forward. Just as Philip had established the mannerist austerity of his Escorial as the appropriate architectural aesthetic for Spain and for exportation to México, he decided that a grid like pattern should characterize New Spain's cities. As such, his urban planning coincided with that of metropolitan Aztec centers rather than the randomness of the streets in Medieval towns, and reflected one of the very few European cities which had been laid out accordingly, namely Pienza in Tuscany. In reality, the King's Ordinances sought to validate both Church and State in New Spain all the while demonstrating that a great world power had come to stay.

“{...} The plan of the place, with its squares, streets and building lots is to be outlined by means of measuring by cord and ruler, beginning with the main square from which streets are to run to the gates and principal roads and leaving sufficient open space so that even if the town grows it can always spread in a symmetrical manner ...”{Ordinance 110}; “At certain distances in the town, smaller, well-proportioned plazas are to be laid out on which the main church, the parish church or monastery shall be built so that the teaching of religious doctrine be evenly distributed...”{Ordinance 120} (Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 2008, pp. 74-75, Sidebar 7: Excepts from King Philip II's 1573 Royal Ordinances Concerning the Laying Out of New Cities, Towns or Villages from The Hispanic American Historical Review 5, no. 2, May, 1922, pps. 249-254)

Puebla, Puebla, Museo de Antropología, sculpture of King Philip II of Spain holding the Golden Fleece Much as the Franciscans had flavored the architecture of the previous century with their monasteries of mendicant preaching (aptly suited for the severity of their task at hand) the foundations of later arriving religious orders such as the Carmelites, Knights Hospitalier, Oratorians and Mercedarians displayed more Mannerist tendencies. On September 28, 1572, the Jesuits arrived in Mexico City where they established their Colegio de San Ildefonso. With their powerful emphasis on education, they introduced their own dynamic brand of religious instruction which gave rise to a vast, two-hundred year building offensive that came to be identified with the Baroque in Colonial Mexico.

Puebla, Puebla, Museo de Antropología, sculpture of King Philip II of Spain holding the Golden Fleece Much as the Franciscans had flavored the architecture of the previous century with their monasteries of mendicant preaching (aptly suited for the severity of their task at hand) the foundations of later arriving religious orders such as the Carmelites, Knights Hospitalier, Oratorians and Mercedarians displayed more Mannerist tendencies. On September 28, 1572, the Jesuits arrived in Mexico City where they established their Colegio de San Ildefonso. With their powerful emphasis on education, they introduced their own dynamic brand of religious instruction which gave rise to a vast, two-hundred year building offensive that came to be identified with the Baroque in Colonial Mexico.

The First Cathedrals

The different campaigns to complete Mexico’s cathedrals mostly took place in the sixteen-hundreds, the century after the Amerindian conversion and King Philip’s decree. In some cases these cathedrals replaced earlier, inadequate structures with edifices worthy of the growing urban areas they serviced, with their remodeling continuing well into the eighteenth century. In each case (possibly with the exception of Oaxaca’s) they reflected the late King’s taste as exemplified by his cherished Escorial, and represent the body of Colonial architecture which visually most closely relates Mexico to Spain and Europe. Trained Mexican architects of this period were familiar with Vitruvius’ Ten Books on Architecture, Leon Battista Alberti’s On the Art of Building (inspired by Vitruvius and published between 1443 and 1452), as well as The Seven Books of Architecture, written by Sebastiano Serlio (1475-circa 1554). Two volumes of this last treatise were first published in Toledo, Spain, in 1552, with the same didactic illustrations as in the original Italian volumes, serving to crystallize Mannerist design.

In 1584 Claudio de Arcienega (circa 1526-1592) was named maestro de obras for Mexico City’s cathedral, dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin. Highly influenced by Juan de Herrera’s austere Escorial, Arciniega was the most prominent Mexican architect of his time and made design alterations to the cathedral which would lead to what one sees today as the largest church of the Americas. Construction continued over a half century after the architect’s death, intensifying in the 1650s under the direction of maestro mayor Luis Gómez de Trasmonte (active, 1656-1684) who in 1667 oversaw the dedication of the interior and South façade.

México, D.F., Catedral Metropolitana de La Asunción de Nuestra SeñoraBelow the twin towers and masking an opulent interior is the cathedral’s façade, in the form of an elongated horizontal rectangle with three portals and matching sets of columns separated by massive buttressing. With the assistance of Rodrígo Diaz de Aguilera, Trasmonte designed the façade's three simple portals, framed by fluted columns and classical capitals of the well-proportioned Doric variety. Between these columns, the central portal encloses sculptures of SS Peter and Paul, carved in 1687 by Miguel and Nicolás Jiménez.

México, D.F., Catedral Metropolitana de La Asunción de Nuestra SeñoraBelow the twin towers and masking an opulent interior is the cathedral’s façade, in the form of an elongated horizontal rectangle with three portals and matching sets of columns separated by massive buttressing. With the assistance of Rodrígo Diaz de Aguilera, Trasmonte designed the façade's three simple portals, framed by fluted columns and classical capitals of the well-proportioned Doric variety. Between these columns, the central portal encloses sculptures of SS Peter and Paul, carved in 1687 by Miguel and Nicolás Jiménez.

Above all three portals are chastely white stone reliefs, set in elegantly shaped eared frames, with the central one depicting the cathedral’s dedicatee, the Virgin of the Assumption, divided into an upper and lower scene. Above, arms extended and holiness radiating forth from her head, Our Lady is transported to heavily glory by jubilant angels playing an assortment of musical instruments. In a Via Crucis below, Jesus hauls his weighty cross amidst other figures, most likely including Simon of Cyrene (depicted in the Fifth Station of the Cross as assisting Christ in raising it). To the left, the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene mourn beside the Lord’s tomb at Golgotha. The composition is vigorous, dynamic, Baroque.

Equally effective are the other two South facing portal reliefs. Above the left one is a kneeling Saint Peter receiving from Christ the Keys to the Kingdom of Heaven. To Peter’s right apostles stand in attendance with intense gazes. To his left, a radiating Christ extends the Keys in his right hand while pointing to the Heavens with his left index finger. The entire scene appears to take place before the very gates of Paradise. Instead, above the right portal is a relief of the early Christian theme known as the Ship of the Church, an interpretive reference to Jesus protecting Peter and the Apostles’ boat on the stormy Sea of Galilee. Peter steers from the stern, apostolic oarsmen row, and from above Christ guides the ship’s course by resting his hand on its single mast.

México, D.F., Castillo Chapultepec, portrait of Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, Bishop of the city of Puebla from 1640 to 1655Austerity came to the equally segmented façade of Puebla’s cathedral, largely completed in the 1640s after the arrival from Spain of the city’s new bishop, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza (1600-1659), a staunch supporter of the Herreran style. A scrupulous and industrious man close to King Philip IV’s court, Palafox was nearly canonized in the second half of the eighteenth century, had the Jesuits not stymied efforts of “The Politician” (Spain’s Bourbon King Charles III, in power 1756-1788) to do so. James Early writes that, during his nine years as Bishop of Puebla, Palafox oversaw the building of a seminary, two colleges, fifty churches and a hundred and forty altarpieces. Settled in 1531not over a Pre-Columbian site and not for the purpose of evangelizing but as a city by Spaniards for Spaniards, it was Palafox who made Puebla what it remains today, namely the architecturally richest colonial city of the New World.

México, D.F., Castillo Chapultepec, portrait of Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, Bishop of the city of Puebla from 1640 to 1655Austerity came to the equally segmented façade of Puebla’s cathedral, largely completed in the 1640s after the arrival from Spain of the city’s new bishop, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza (1600-1659), a staunch supporter of the Herreran style. A scrupulous and industrious man close to King Philip IV’s court, Palafox was nearly canonized in the second half of the eighteenth century, had the Jesuits not stymied efforts of “The Politician” (Spain’s Bourbon King Charles III, in power 1756-1788) to do so. James Early writes that, during his nine years as Bishop of Puebla, Palafox oversaw the building of a seminary, two colleges, fifty churches and a hundred and forty altarpieces. Settled in 1531not over a Pre-Columbian site and not for the purpose of evangelizing but as a city by Spaniards for Spaniards, it was Palafox who made Puebla what it remains today, namely the architecturally richest colonial city of the New World.

Over a century after Palafox’s death, Francisco Fabián y Fuero, Puebla’s bishop from 1765-1773, nucleated his own library with some five thousand volumes which Palafox had donated to the Seminario Tridentino, to form the glorious Biblioteca Palafoxiana. Because the state of Puebla was the agriculturally richest in Mexico, Palafox earned healthy profits to spend on the erection of the city’s cathedral, over whose dedication to the Virgin Immaculate he presided on April 18, 1649. Less than two months later the Bishop left for Osma, Spain, never again to return to Mexico.

The façade of Palafox’s cathedral forms a vertical rectangle, accentuating its height in a much smaller zócalo than that of its cousin in Mexico City. Its black limestone is more somber than the gray and buff colored basalt employed for the capital’s cathedral and contrasts sharply with the façade’s stark white reliefs. The three West facing portals were begun by Francisco Gutiérrez Caballo (circa 1616-1670) and completed by Vicente Barroso de la Escayola (? - 1692). Predictably, Saints Peter and Paul flank the central Puerta del Perdón with SS Joseph and James the Greater directly above. All four sculpture were carved in 1662, presumably by Juan de Solé González. Above Peter and Paul are reliefs of vases with lilies, symbols of the Immaculate Conception.

Puebla, Puebla, Catedral de La Inmaculada Concepción, façade, right portal main relief, Ecstasy of St. Teresa of Avila The refined and energetic reliefs above the façade’s lateral portals and are also attributed to Solé González, who was undoubtedly responsible for other church reliefs about the city. The left portal showcases Saint Rose of Lima (1586-1617), canonized by Pope Clement X in 1671 as the very first saint of the Americas. Often depicted upholding the Christ Child amid a bouquet of roses in her right hand, here she is shown genuflecting before Mary and the infant Jesus. To the right stands Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), her Ecstasy portrayed by an angel delivering an immense arrow into her heart while fellow angels uphold her lacerated body.

Puebla, Puebla, Catedral de La Inmaculada Concepción, façade, right portal main relief, Ecstasy of St. Teresa of Avila The refined and energetic reliefs above the façade’s lateral portals and are also attributed to Solé González, who was undoubtedly responsible for other church reliefs about the city. The left portal showcases Saint Rose of Lima (1586-1617), canonized by Pope Clement X in 1671 as the very first saint of the Americas. Often depicted upholding the Christ Child amid a bouquet of roses in her right hand, here she is shown genuflecting before Mary and the infant Jesus. To the right stands Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), her Ecstasy portrayed by an angel delivering an immense arrow into her heart while fellow angels uphold her lacerated body.

Emanating from Saint Teresa’s face is a banderole on which can be deciphered the words Misericordia dei in aeternum cantabo (Forever will I will sing of the mercies of the Lord), a phrase extracted from the Catholic liturgy for her feast day (Communion antiphon number 89). This same inscription appears in the only lifetime portrait of the saint painted by Brother Juan de la Miseria at the time she was 61. The image was popularized in Europe and likely in New Spain by an engraving after the painting, executed by the Flemish engraver Hieronymous Wierix (1553-1619), known for his prolific prints of saints, religious, allegorical, and political themes.

Also designed by the Italian architect Vicente Barroso de Escayola, Morelia’s Cathedral is considerably less somber than those of Mexico City and Puebla. Named for the Transfiguration of Christ and dedicated in 1705, it was a favorite of scholar-writer Trent Elwood Sanford, whose described it as “the most beautiful of all the cathedrals of Mexico”. The massive bases of its bell-towers are offset by twin airy belfries aloft; its generally restrained classicism is enlivened by the use of trachyte stone, porphyritic in texture and light pinkish-brown in hue. Though fundamentally a low rising structure, the sense of elevation is enhanced not only by the soaring 200 ft. towers but by the marked height differential between the façade’s central portal and that of its lateral ones.

The reliefs at Morelia are many and superb. Atop the central portal is the Transfiguration of Christ, a priceless and didactic depiction of this infrequently rendered theme. As Christ begins to magically radiate, God the Father (shown above) appears and audibly addresses him as son. The Old Testament prophets Moses and Elijah stand to either side of Jesus, while his apostles Peter, John and James the Greater (all three of whom accompanied him to Mount Transfiguration) are shown below, witnesses to this moment of irrevocable proof of Christ’s divinity. Over the side portals are elaborate depictions of the Adoration of the Magi (left) and the Adoration of the Shepherds (right), while East and West doorways bear reliefs of Our Lady of Guadalupe and Saint Joseph with baby Jesus, respectively.

Morelia, Michoacán, Catedral de La Transfiguración de Cristo, façade, central portal relief detail, Transfiguration of Christ with Old Testament prophets Moses & ElijahThe four other original diocesan cities where cathedrals were erected are Guadalajara (Jalisco), Oaxaca (Oaxaca), San Cristóbal de las Casas (Chiapas), and Mérida (Yucatán). Whereas the façade of Guadalajara’s the Assumption of Our Lady was completely rebuilt in the late seventeen hundreds, Mérida’s San Idelfonso is the only cathedral to be completed before 1600. Its impressive dome bears the date of 1598 as well as the name of its second architect, Juan Miguel de Agüero, who arrived from Havana, Cuba, to complete the project. In varying ways, all seven cathedrals not only display broad naves and grand cupolas but side aisles with rows of chapels which perpetuate the “cryptocollateral” church plan that in his 1948 publication Mexican Architecture of the Sixteenth Century, George Kubler proposed was espoused by the Dominicans in some of their late sixteenth century Oaxacan conventos.

Morelia, Michoacán, Catedral de La Transfiguración de Cristo, façade, central portal relief detail, Transfiguration of Christ with Old Testament prophets Moses & ElijahThe four other original diocesan cities where cathedrals were erected are Guadalajara (Jalisco), Oaxaca (Oaxaca), San Cristóbal de las Casas (Chiapas), and Mérida (Yucatán). Whereas the façade of Guadalajara’s the Assumption of Our Lady was completely rebuilt in the late seventeen hundreds, Mérida’s San Idelfonso is the only cathedral to be completed before 1600. Its impressive dome bears the date of 1598 as well as the name of its second architect, Juan Miguel de Agüero, who arrived from Havana, Cuba, to complete the project. In varying ways, all seven cathedrals not only display broad naves and grand cupolas but side aisles with rows of chapels which perpetuate the “cryptocollateral” church plan that in his 1948 publication Mexican Architecture of the Sixteenth Century, George Kubler proposed was espoused by the Dominicans in some of their late sixteenth century Oaxacan conventos.

“The cathedrals of New Spain were Mexican mainly by geography; they are truly colonial architecture. Moved into position on the main plaza, flanked by the Palacio de Gobierno, the cathedral throws into relief the Mexican quality of other buildings. And they have other messages. They sound a note of temporal authority, reminding us that the king of Spain was also head of the church in the Americas, and that the archbishop was as much his emissary as was the viceroy. They testify to the ascendancy of the secular clergy, and to their orientation to a Spanish congregation.” (Weismann, Elizabeth Wilder. Art and Time in Mexico: Architecture and Sculpture in Colonial Mexico, Harper & Row, New York, 1985, p. 153)

From St. Peter’s to Tlatelolco: Bernini’s New World Legacy

The aesthetic impact of the Escorial was accompanied by a revolutionary Italian contribution to Spanish and subsequently Mexican architecture, and one which in Europe immediately inaugurated the high Baroque. In 1624 Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) completed the designs for his baldachin in Rome’s St. Peter’s Basilica. Features of this swirling, spiraling structure were widely implemented all about seventeenth century Spain and thereafter in the form of the salomónica, or Solomonic column, so called because of the presumed use of such columns in the ancient Temple of Solomon, according to Hebrew scripture built on Mt. Moriah in Jerusalem in the 10th century BC. Solomonic columns soon immigrated to Mexico, where they found their way onto church façades, retablos, and bell-towers.

Irapuato, Guanajuato, La Misericordia, façade salomónicasIn fact, Mexican ecclesiastical architecture of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries abound with salomónicas, often coated in helicoidal, vegetal relief. The bell-tower of La Expectación de la Virgen, San Luis Potosí’s cathedral, has three types of Solomonic columns, as does the sumptuous façade of Santo Domingo in San Cristóbal de las Casas (Chiapas). The lofty bell-towers of San Cristóbal in Puebla city bear slender salomónicas whereas the lower level of the façade of Atlixco’s Capilla de la Tercera Orden (Puebla state) manifests pairs of bulbous Solomonic columns, whose spirals are heavily laden with vegetal carvings. Countless Baroque altarpieces display dazzling salomónicas, including those of the high altar of the parish church at San José Chiapa (Puebla), unique for having been cut entirely from alabaster stone.

Irapuato, Guanajuato, La Misericordia, façade salomónicasIn fact, Mexican ecclesiastical architecture of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries abound with salomónicas, often coated in helicoidal, vegetal relief. The bell-tower of La Expectación de la Virgen, San Luis Potosí’s cathedral, has three types of Solomonic columns, as does the sumptuous façade of Santo Domingo in San Cristóbal de las Casas (Chiapas). The lofty bell-towers of San Cristóbal in Puebla city bear slender salomónicas whereas the lower level of the façade of Atlixco’s Capilla de la Tercera Orden (Puebla state) manifests pairs of bulbous Solomonic columns, whose spirals are heavily laden with vegetal carvings. Countless Baroque altarpieces display dazzling salomónicas, including those of the high altar of the parish church at San José Chiapa (Puebla), unique for having been cut entirely from alabaster stone.

The pairs of Solomonic columns beside the sculpture on the second story of the West façade of Mexico City’s cathedral are considered to be the first exterior use of this architectural order in Mexico. Nearby at Tlatelolco, the site of the remarkable Aztec marketplace eternalized by the admiring words of Spanish conquistador-chronicler Bernal Diaz (1492-1584) in his The True History of the Conquest of New Spain (1568), the lost high and nave altars of the church of Santiago may have represented the first interior implementation of the salomónica. In Noticias sobre la destrucción del retablo de Tlatelolco José Guadalupe Victoria asserts that the high altar's Solomonic columns postdate the altar itself, yet it is unknown when they may have been added. The configuration of the ensemble is only known by way of a lithograph published in 1861 by Manuel Ramírez Aparicio (1831-1867) in his book Los conventos suprimidos de México. Judging from this image the altarpiece appears breathtaking. Enormous, it stood four stories high, with statuary and paintings interspersed on all levels in an expansive, yet spatially ordered format.

In scrutinizing the image of the altarpiece in Aparicio’s book, it appears as though two pairs of matching Solomonic columns enclosed sculptures of saints to either side of the tabernacle and central statues. Their pairing continued up to the fourth tier, where a dominant rendering of the Crucifixion is also framed by statues and accompanying salomónicas. Still situated in the otherwise vacant apse is all that remains (in the current church) of this masterpiece, the powerful relief of Santiago Mataíndios, namely the biblical Saint James the Greater, son of Zebedee and brother to John the Evangelist. The lithographic reproduction shows the relief as having been the central panel to the retablo’s second story. This is precisely where the saint to whom a high altar was dedicated would have been positioned per the 1563 dictates of the Twenty-Fifth Council of Trent, issued during Counter-Reformation Europe in an effort to reaffirm Catholic orthodoxy.

Photograph of the lithograph depicting the nave, cupola and destroyed high altar at Santiago Tlatelolco, México, D.F., from the 1861 publication Los conventos suprimidos de México by Manuel Ramírez AparicioThe splendid panel of Santiago is action-packed, an early testimony to the Baroque in Mexico. Flashing his cape, wielding his sword, and wearing his pilgrim’s cap, the patron saint of Spain rides his white charger over fellow soldiers and vanquished Indians in the melee of battle. He is the embodiment of Spain’s military and religious supremacy; the unity of the spiritual and the armed, as reflected by the Knights of Santiago, the Military Order of Saint James of the Sword, founded in the twelfth century to protect Christian pilgrims against Muslim marauders as the former headed to and from the tomb of Saint James at Compostela (Galicia). It was his name, "¡Santiago!", which Spanish soldiers exclaimed when about to engage their enemy.

Photograph of the lithograph depicting the nave, cupola and destroyed high altar at Santiago Tlatelolco, México, D.F., from the 1861 publication Los conventos suprimidos de México by Manuel Ramírez AparicioThe splendid panel of Santiago is action-packed, an early testimony to the Baroque in Mexico. Flashing his cape, wielding his sword, and wearing his pilgrim’s cap, the patron saint of Spain rides his white charger over fellow soldiers and vanquished Indians in the melee of battle. He is the embodiment of Spain’s military and religious supremacy; the unity of the spiritual and the armed, as reflected by the Knights of Santiago, the Military Order of Saint James of the Sword, founded in the twelfth century to protect Christian pilgrims against Muslim marauders as the former headed to and from the tomb of Saint James at Compostela (Galicia). It was his name, "¡Santiago!", which Spanish soldiers exclaimed when about to engage their enemy.

“Already in 822 at the battle of Clavijo, Saint James intervened when King Ramiro of the Asturias was losing against the Moors. Suddenly, a figure on a white horse appeared, and turned the struggle in favor of the Christians. He told the king that Christ himself ‘gave Spain for me to watch over her and protect her from the hands of the enemies of the faith’. This was the first appearance of Santiago Matamoros, St. James Moor Slayer. Thereafter he returned time and again to save Christian Spain from disaster.” (Wheatcroft, Andrew. Infidels: A History of the Conflict between Christendom and Islam, Random House, New York, 2005, p. 86)

At Tlatelolco it is not, however, St. James the Moor Slayer who commands the apse of the church, but rather James the Indian Killer. Said to have appeared no less than fourteen times in the New World between 1518 and 1892, Santiago interceded on behalf of the conquistadores at Sunturhuasi in Cuzco, Peru, during the 1536 Inca siege, just as he did at the battle for Acoma, New Mexico, in 1595. Eventually, Santiago would become an Amerindian idol and protector, with post Tlatelolco imagery of him reverting to James the Moor Slayer, whose miraculous appearance a Clavijo centuries earlier had sanctified the 670-year Christian Reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Father Juan de Torquemada (circa 1562-1624), who oversaw the rebuilding of the Tlatelolco church, witnessed the retablo’s installation in 1610, and in his Monarquía Indiana (published in three volumes in Seville, Spain, in 1615) cited the master carver of the Santiago Mataíndios relief as a certain indigenous by the name of Miguel Mauricio. Above Santiago Mataíndios, on the third tier of the Tlatelolco retablo, appears St. Francis of Assisi, uplifting his robe to protect his followers. The entire structure is crowned by God the Father in the attic.

Tlatelolco's high altar was constructed by the same workshop responsible for the late sixteenth century one in the Franciscan convento of San Bernardino de Sena in Xochimilco (a Southern district of Mexico City), one of a handful of extant sixteenth century Mexican retablos. Unlike Xochimilco's, however, that at Tlatelolco came to bridge Renaissance and Baroque aesthetics with the novel vitality of its salomónicas. The original Franciscan Colegio Imperial de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco had been founded as early 1536 for the training of indigenous boys (largely sons of native nobility) for the priesthood. The enterprise bore little fruit and was eventually abandoned. It was after the Reform Laws of 1859 in which liberals succeeded, if only temporarily, in their secularizing efforts, that this great treasure of colonial art fell victim to a fire. Its loss is immeasurable.

A Popular Baroque

The same century which introduced European inspired Baroque cathedrals also saw the rapid rise of a “popular” style of art and architecture, rooted in the free and innate creativity of the native hand. The term ‘popular’ is less than precise if not somewhat cryptic. Certainly not meant to convey the ordinary or pedestrian, Mexican popular architecture of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was both original and regional. Gaining a sensibility for this Puebla, Puebla, San Cristóbal, cupolaaesthetic is essential to appreciating the Colonial Mexico, as is spotting tequítqui or scrutinizing the churrigueresque. The following adjectives somewhat describe this popular art form: ornamental, decorative, eclectic, eccentric, idiosyncratic, unofficial, vernacular, innocent, naïve, folkish, rustic, authentic.

Puebla, Puebla, San Cristóbal, cupolaaesthetic is essential to appreciating the Colonial Mexico, as is spotting tequítqui or scrutinizing the churrigueresque. The following adjectives somewhat describe this popular art form: ornamental, decorative, eclectic, eccentric, idiosyncratic, unofficial, vernacular, innocent, naïve, folkish, rustic, authentic.

Sometimes thought of more as fashion than style, Mexican popular architecture looked to stucco as a more workable medium than stone. Described by Pál Keleman as having as a “dough-like quality” with “a malleability that suggests wax or marzipan”, the art historian describes certain columnar details as if “braided pastry had been translated into stucco”. While the architectural plans for many colonial buildings still exist in the Archive of The Indies in Seville, Spain, usually there were no specific designs for their exterior decoration. Hence, the results could be unhampered, even jaw dropping, as anonymous artisans plastered countless combinations of stucco forms to architectural surface space.

“Usually in Mexico a popular Baroque façade is based on one of the orthodox plans -- the structural division by columns and cornices, the framing of doors and windows, the figures of saints between the columns, the large central relief, and so on. But as the detail is executed it gets out of control, and seems to grow and take over the structure, too big, too much, and extending too riotously over everything.” (Weismann, Elizabeth Wilder. Art and Time in Mexico: From the Conquest to the Revolution, Harper & Row, Publishers, New York, 1985, pps. 196-7)

Elizabeth Wilder Weismann made another astute point. The artistic development of a particular culture, once subdued by a more dominant one, tends over time to reflect the traits of its conqueror. The very opposite took place in Mexico with respect to preeminent Spain. As Mexico’s viceregal period progressed, more and more of the resultant architecture actually reflected greater rather than less pre-Conquest attributes. In large part this was due to an eventual relaxation of censorship and super-direction on behalf of the monastics over the entire scope of imagery produced by the indigenous. By 1600 all learned techniques and styles were European, the religious conquest of central Mexico was complete, the Regular clergy had largely been replaced by seculars, and the Church could breathe easier about latent native aesthetics within the context of indigenous apostasy.

Hueyotlipan, Tlaxcala, San Ildefonso, bell-tower relief, Archangels with House of Hapsburg bicephalous eagleAlso true is that the regions of New Spain which were home to the most advanced and populated pre-Colombian cultures are the same which produced the greatest quality and quantity of post-conquest colonial art and architecture. The state of Puebla was the wellspring for the popular Baroque style of intaglio, followed in activity by the bordering states of Oaxaca, Tlaxcala, Morelos, and México. In these regions pre-Conquest stylistic autonomy resurfaced more wittingly and less clandestinely than in the previous century, where it had taken the form of Indochristian art, a de facto, syncretic accommodation whose manifestations could only peek out from behind Spanish redaction.

Hueyotlipan, Tlaxcala, San Ildefonso, bell-tower relief, Archangels with House of Hapsburg bicephalous eagleAlso true is that the regions of New Spain which were home to the most advanced and populated pre-Colombian cultures are the same which produced the greatest quality and quantity of post-conquest colonial art and architecture. The state of Puebla was the wellspring for the popular Baroque style of intaglio, followed in activity by the bordering states of Oaxaca, Tlaxcala, Morelos, and México. In these regions pre-Conquest stylistic autonomy resurfaced more wittingly and less clandestinely than in the previous century, where it had taken the form of Indochristian art, a de facto, syncretic accommodation whose manifestations could only peek out from behind Spanish redaction.

Thus, the unbridling of the indigenous hand in the seventeenth century resulted in some of the country’s most unrestrained architecture, fructified by a vast pool of repressed creativity which had belied the muting effects of lapsed time. Architectural solutions were subordinated to ornamental bedazzlement, as structural features evanesced beneath strapwork intricacy. Detail upon detail, in seemingly microscopic subsets, flowed outwards from church façades. The mobility of line, a Baroque hallmark, swelled into a frenzy of form as New Testament scenes, related Christian iconography, apostles, evangelists, saints and archangels celebrated their newfound freedom in stucco form.

Santa Cruz, Tlaxcala, Santa Inés, high altar, lower story, tabernacle arch cherubimAngels in particular covered retablo and church façades, at times seemingly infinite in number. Such a boisterous abundance of cherubs and seraphs thronging about central reliefs begs the question from where did these jolly youngsters come. Just as Flemish manuscripts had inspired sixteenth century convento wall murals, Kelemen suggests that the Low Countries had an important hand in the New World arrival of these angelic imps by way of “Flemish emblem books and albums of sketches {which} contain many small engravings featuring a jolly company of baby angels about the child Mary or the Infant Jesus.” (Kelemen, Pál. Baroque and Rococo in Latin America, MacMillan Publishers, New York, 1951, p. 218)

Santa Cruz, Tlaxcala, Santa Inés, high altar, lower story, tabernacle arch cherubimAngels in particular covered retablo and church façades, at times seemingly infinite in number. Such a boisterous abundance of cherubs and seraphs thronging about central reliefs begs the question from where did these jolly youngsters come. Just as Flemish manuscripts had inspired sixteenth century convento wall murals, Kelemen suggests that the Low Countries had an important hand in the New World arrival of these angelic imps by way of “Flemish emblem books and albums of sketches {which} contain many small engravings featuring a jolly company of baby angels about the child Mary or the Infant Jesus.” (Kelemen, Pál. Baroque and Rococo in Latin America, MacMillan Publishers, New York, 1951, p. 218)

The following is a list of a number of 17th century churches whose façades far outshine the rest of the complexes for their lavish, Popular Baroque embellishment: Santa Bárbara Tlacatempan (México), San Antonio Texcoco (México), San Miguel Arcángel Coatlinchán (México), La Tercera Orden Atlixco (Puebla), San Juan Evangelista Ahuacatlán (Puebla), San Mateo Chignautla (Puebla), San Pedro Colomoxco (Cholula, Puebla), the parish church of Santa María Atlihuetzía (Tlaxcala), San Martín Jonacantepec (Morelos), San Martín Tlayacapan (Morelos), La Soledad in Oaxaca city, San Matías Pinos (Zacatecas), and the enchanting hacienda chapels at Santiago Tetlapayac (Hidalgo) and Molino de Flores (México).

The Hacienda as Architecture

It should be noted that the earlier cited hacienda system resulted in some notable colonial architecture. Based on the Andalusian farm-estate, haciendas were diverse in what they produced, depending on geography and climate. There were, for instance, cattle and horse haciendas, silver refining haciendas, while others were dedicated to agricultural products such as cotton, sugar, sisal, corn, grain, even mezcal. This manifold production is reflected in the accommodating building types. In the eighteenth century when Santiago Tetlapayac (Hidalgo) began making the widely popular fermented alcoholic drink known as pulque (derived from the agave cactus), the specific structure known as a tinacal had to be erected. Unique to the “hacienda pulquera” as the capilla abierta is to the convento, linguistically the word derives from the conjoined Náhuatl “tina” and “calli”, literally meaning “house of vats”. In fact, the tinacal was the storage facility for large barrels of pulque prior to their distribution.

Santiago Tetlapayac, Hidalgo, hacienda chapel, nave & altarBoth a work compound and leisure residence, the hacienda also contained a chapel which along with the casa grande often represents the finest architectural feature on the premises. As with grand private homes in city centers, hacienda chapels were more on a domestic scale, some of which still display their ornate gilded retablos, such as at Pabellón de Hidalgo (Aguascalientes), El Cabezón (Jalisco), Pozo del Carmen and Bledos (both San Luis Potosí) or, once again, Santiago Tetlapayac (Hidalgo). Although many are post-Colonial, dating to the late nineteenth or even early twentieth centuries, numerous colonial haciendas and their chapels survive.

Santiago Tetlapayac, Hidalgo, hacienda chapel, nave & altarBoth a work compound and leisure residence, the hacienda also contained a chapel which along with the casa grande often represents the finest architectural feature on the premises. As with grand private homes in city centers, hacienda chapels were more on a domestic scale, some of which still display their ornate gilded retablos, such as at Pabellón de Hidalgo (Aguascalientes), El Cabezón (Jalisco), Pozo del Carmen and Bledos (both San Luis Potosí) or, once again, Santiago Tetlapayac (Hidalgo). Although many are post-Colonial, dating to the late nineteenth or even early twentieth centuries, numerous colonial haciendas and their chapels survive.

“The hacienda is disappearing as an institution, obsolete and irreconcilable with the Mexico of today, but religion persists to the present in the hearts of the peasants (now themselves the owners of small plots of land) who preserve the Catholic faith, the religion that formerly reconciled the owners and peons who lived and died in the hacienda.” (Nierman, Daniel and Vallejo, Ernesto H. The Hacienda in Mexico, translated by Mardith Schuetz-Miller with a foreword by Elena Poniatowska, University of Texas Press, Austin, 2003, p. 54)

Two Brilliant Gems

The most lavish sixteenth century expressions of Popular Baroque, are found inside two Dominican chapels. The one dedicated to the Black Friar's cult of the Rosary in the church of Santo Domingo in the city Puebla (erected 1650-1690) was described at its inauguration as “the eighth wonder of the world”, and rhapsodized by Manuel Toussaint as “the climax of a type of church which represents the Mexican mood of that time in an extraordinary way.” (Toussaint, Manuel, Paseos Coloniales, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Imprenta Universitaria, México, D.F., 1962, p. 137 personal translation). As with its eighteenth century Rosary Chapel relative at Santo Domingo Oaxaca, nave, vaults, and cupolas are encrusted in stucco ornamentation beneath a mesh of gold leaf strapwork.

Entered through the South transept of the church of Santo Domingo church, the chapel’s walls are lined with paintings of the Life of Our Lady by José Rodríguez de Carnero (1649-1725). In the center of each of the nave vaults are reliefs of Faith, Hope and Charity, the Three Theological Virtues of the Catholic faith. In its large, lower niche, the central baldachin houses the statue of Our Lady of the Rosary which St. Joseph appears above between pairs of Salomónicas. The opulent cupola is divided into eight partitions by helicoidal columns with vegetal relief. Facing the nave is Divine Grace while incarnations of the Seven Gifts of the Holy Ghost fill each of the other seven domal segments. Resting along the drum are the Four Evangelists and sixteen female saints while the pendentives are occupied by archangels. In the low rising choir loft God the Father is surrounded by a grouping of prancing angels, joyfully playing their musical instruments.

“When we visit the chapel in the early afternoon, while the light floods through the windows of the cupola, our spirits soar free within its compass and we are transported to the days at the end of the seventeenth century when multitudes gathered in the churches to participate in the splendid ceremonies.” (Toussaint, Manuel. Colonial Art in Mexico, translated and edited by Elizabeth Wilder Weismann, University of Texas Press, Austin and London, 1967, p. 205)

Tlacolula, Oaxaca, La Asunción, Capilla del Santo Señor, choir loftOn a smaller scale, the chapel of The Holy Father in the Dominican church of La Asunción, Tlacolula (Oaxaca), is a sixteen-hundreds Baroque jewel. One accesses the chapel from the South side of the Church nave through a gilded portal and magnificent grille-worked door. Immediately above is the sotocoro arch with its beautiful gold inlays and choir loft balcony, off of which at times one sees suspended a large, gilded wood pendant in the form of the Ship of the Church. Statues of the martyred SS Denis and John the Baptist uphold their decapitated heads to each side of the sotocoro while a relief of St. Joseph and the Christ Child fill the center of the loft’s back wall. The short nave bears paintings of the Life and Passion of Christ, its double vaulted ceiling overlaid by polychromed strapwork. Wonderful grille work reappears in the pulpit on the right side of the chancel arch. The high altar is a Neoclassical eyesore, although it houses a beautiful wood Crucifixion which hangs beneath a halo of angel heads encircling the Holy Ghost. To either side of the altar within the sanctuary are rich reliefs of the Deposition and Entombment of Christ. Above each and webbed over the presbytery clerestory are gilded vines, off of which hang clusters of grapes, and on which stand festive cherubs.

Tlacolula, Oaxaca, La Asunción, Capilla del Santo Señor, choir loftOn a smaller scale, the chapel of The Holy Father in the Dominican church of La Asunción, Tlacolula (Oaxaca), is a sixteen-hundreds Baroque jewel. One accesses the chapel from the South side of the Church nave through a gilded portal and magnificent grille-worked door. Immediately above is the sotocoro arch with its beautiful gold inlays and choir loft balcony, off of which at times one sees suspended a large, gilded wood pendant in the form of the Ship of the Church. Statues of the martyred SS Denis and John the Baptist uphold their decapitated heads to each side of the sotocoro while a relief of St. Joseph and the Christ Child fill the center of the loft’s back wall. The short nave bears paintings of the Life and Passion of Christ, its double vaulted ceiling overlaid by polychromed strapwork. Wonderful grille work reappears in the pulpit on the right side of the chancel arch. The high altar is a Neoclassical eyesore, although it houses a beautiful wood Crucifixion which hangs beneath a halo of angel heads encircling the Holy Ghost. To either side of the altar within the sanctuary are rich reliefs of the Deposition and Entombment of Christ. Above each and webbed over the presbytery clerestory are gilded vines, off of which hang clusters of grapes, and on which stand festive cherubs.

Tlacolula, Oaxaca, La Asunción, Capilla del Santo Señor, West transept vaulting, St. Peter CrucifiedThe narrow transept and the corresponding altars, each fitted between return-wall retablos, are exquisitely Baroque. The right transept altar is dedicated to the previously described Christ of Patience. To His side are the martyred SS Sebastian and Lawrence and above SS Philip and James the Greater, while positioned to the right is an elegant, free-standing statue of St. Joseph from the Flight into Egypt. The opposite transept is consecrated to Our Lady of the Assumption and is flanked by SS Simon and Bartholomew. Above the return retablos in the left transept are striking reliefs of SS Andrew and Peter, both crucified, the latter upside-down per longstanding Church tradition. Explicitly, the poignant story of Peter’s request to be crucified in an inverted manner is told by the early Christian theologian Origen of Alexandria (185-254) and documented in the second volume of Ecclesiatical History, written by the fourth century Roman historian and bishop of Caesarea, Eusebius Pamphili (260/165-circa 340).

Tlacolula, Oaxaca, La Asunción, Capilla del Santo Señor, West transept vaulting, St. Peter CrucifiedThe narrow transept and the corresponding altars, each fitted between return-wall retablos, are exquisitely Baroque. The right transept altar is dedicated to the previously described Christ of Patience. To His side are the martyred SS Sebastian and Lawrence and above SS Philip and James the Greater, while positioned to the right is an elegant, free-standing statue of St. Joseph from the Flight into Egypt. The opposite transept is consecrated to Our Lady of the Assumption and is flanked by SS Simon and Bartholomew. Above the return retablos in the left transept are striking reliefs of SS Andrew and Peter, both crucified, the latter upside-down per longstanding Church tradition. Explicitly, the poignant story of Peter’s request to be crucified in an inverted manner is told by the early Christian theologian Origen of Alexandria (185-254) and documented in the second volume of Ecclesiatical History, written by the fourth century Roman historian and bishop of Caesarea, Eusebius Pamphili (260/165-circa 340).

With archangels in the pendentives, the chapel dome is an eight-sectional masterwork, each of its ribs adorned with vegetal relief and heads of cherubim. An enormous Via Crucis fills the top with Christ bearing his massive cross before a background of heavenly golden stars. He is encircled by eight saints including SSSS Catherine of Siena, Rose of Lima, Dominic of Gúzman and the winged Vicente Ferrer, all Mexican favorites and each a frequent resident in Dominican foundations. Compact in scale yet grand in imagination, the chapel of El Santo Señor is a condensed treasure trove of colonial artifacts and architecture.

From Talavera to Tlaxcala

Another material effectively utilized by the popular Baroque style was the azulejo. Not to be confused with the Spanish word “azul” for the color “blue”, an azulejo is an earthenware tile painted and enameled with rich colors in the tradition of where the process began, namely Talavera de la Reina (Castilla-La Mancha), Spain. By the second half of the seventeenth century Talavera tiled church and palace façades were not uncommon, while in the eighteenth the fashion grew in popularity. Much marvelous tile work may be found in the small state of Tlaxcala, while its neighbor, Puebla, lead the country in the manufacture of ceramics and became the focal point of this aesthetic application.

Puebla, Puebla, El Carmen, Tercera Orden, façade, mixtilinear motif & azulejos insigniaThe Carmelite foundation (1625-1634) in the city of Puebla has some particularly refined azulejo work. In the second story of the church’s adjacent Chapel of the Third Order a frame of multifoil, white-painted stucco encloses a Carmelite emblem, a multi-colored tiled crown, and a blue and white tiled cross -- all on the facade's checkered red and yellow azulejo backdrop. Not far from El Carmen in the city center of Puebla is another 17th century azulejo façade, that of San José. In contrast to a red and white background, blue and gold tilework cover the first story columns encasing SS Peter and Paul as well as the second story pilasters framing the stucco relief of St. Joseph and the Christ Child. The church’s dome and lantern are also covered in like azulejos.